Facts About Absinthe

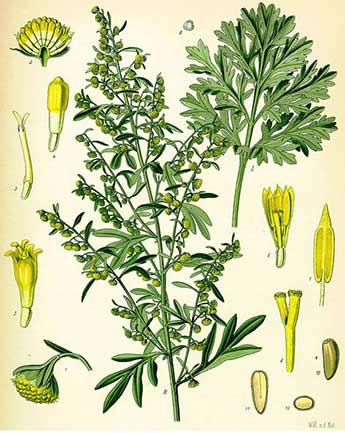

Absinthe is a high-proof distilled spirit (usually between about 55–72% ABV) that takes its name from the Latin name for wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Despite the name and the absolutely essential wormwood, perhaps the most characteristic flavor actually comes from anise (Pimpinella anisum), and to some extent also from fennel (Foeniculum vulgare). These three herbs, not essences or other types of flavorings, form the foundation of true absinthe and are sometimes referred to as "the holy trinity of absinthe".

The most important point, however, is that absinthe is not just about flavoring alcohol, as in the production of aquavit or schnapps, but that the mixture must be distilled (yet again, so to speak). Thanks to this distillation, much of wormwood’s otherwise distinctive bitterness disappears, resulting in a much milder and fresher taste. Anise, as mentioned, tends to dominate flavor-wise, but in order to produce a truly good absinthe, one always strives for a well-balanced interplay between these three main ingredients (and of course, other herbs as well).

Other flavorings, often added as a secondary seasoning after distillation, typically include Roman wormwood (Artemisia pontica), hyssop, coriander, licorice root, star anise (Illicium verum), and peppermint. Even herbs as common in Sweden as fresh parsley and nettles can be used. The chlorophyll in fresh (green) herbs is, incidentally, what gives absinthe its characteristic and usually green color (absinthe verte). However, there are also absinthes that are completely colorless (blanche or la bleue), as well as a few rare red ones (rouge). The general rule, though, is that any coloring should come exclusively from plants or plant parts. Likewise, there is a fairly strict rule that absinthe is never pre-sweetened, neither with sugar nor with other sweeteners.

Absinthe should never (!) be consumed undiluted. Traditionally, it is mixed with about three to five parts ice-cold water to one part absinthe (which results in a final drink with an alcohol content of around 12–20% vol (22–40 proof). Absinthe can also be used as an excellent ingredient in various drinks and cocktails.

Production

What distinguishes a genuine, authentic absinthe from so-called fauxsinthes (often also referred to as crapsinthes) or the so-called bohemian style or Czech varieties (see below under The Comeback) is that true absinthe is made by infusing strong neutral alcohol (80–96%) with at least the three main ingredients: wormwood, anise, and fennel. After this, the infused mixture must be distilled. This is the absolutely crucial step. As for the counterfeit versions, they are often merely infused and filtered. In extreme cases, essences are used, and in the worst cases even chemicals are added for both taste and color, but at that point, it can no longer be called absinthe at all. These imitations are also significantly cheaper to produce, yet they are very often sold at roughly the same price as the genuine product. Sometimes they are even more expensive. In plain terms, it’s nothing but fraud!

What distinguishes a genuine, authentic absinthe from so-called fauxsinthes (often also referred to as crapsinthes) or the so-called bohemian style or Czech varieties (see below under The Comeback) is that true absinthe is made by infusing strong neutral alcohol (80–96%) with at least the three main ingredients: wormwood, anise, and fennel. After this, the infused mixture must be distilled. This is the absolutely crucial step. As for the counterfeit versions, they are often merely infused and filtered. In extreme cases, essences are used, and in the worst cases even chemicals are added for both taste and color, but at that point, it can no longer be called absinthe at all. These imitations are also significantly cheaper to produce, yet they are very often sold at roughly the same price as the genuine product. Sometimes they are even more expensive. In plain terms, it’s nothing but fraud!

(Click the image above to watch a YouTube video about the production process (with Ted Breaux))

The Comeback

(Absinthe 2.0)

Here comes a bit more history, but on the other hand, all facts are history as well, and since this will now be about what happened from the 1990s onward, I’m putting it on this page.

As I mentioned earlier, far from all countries banned absinthe, and Pernod Fils (the most popular and appreciated brand during la belle époque) moved its production to Tarragona in Spain. However, the largest market base was gone, as it had mainly been French. Still, Pernod Fils fought on bravely until declining sales finally made them give up and stop producing absinthe in the mid-1960s.

Another country, and in this context quite an important one, that also escaped the absinthe bans was Czechoslovakia. When the so-called Velvet Revolution took place in 1989, the country’s enterprise picked up again after decades of state-communist oppression. One of the companies that began to emerge was a small distillery where the inventive Radomill Hill started producing his own version (?!) of absinthe, Hill’s Absinth, spelled without a final -e. (Picture to the right.) This distinctive spelling would later come to represent Czech, or so-called "bohemian style", absinths. But it isn’t just the name that gives away that these differ somewhat from the classic absinthes. Most of all, these Czech variants are produced without distillation and generally with essences. In addition, they often lack anise entirely (or even star anise), which means the drink does not turn cloudy (opalesce) when mixed with cold water. The bitter taste (one of the reasons modern absinthe gained a rather poor reputation in terms of flavor) and the absence of opalescence may have been contributing factors to the now infamous abuse (!) of setting absinthe on fire. This new "absinth ritual", however, has no historical basis whatsoever, and no evidence has been found that it was practiced at all before the 1990s. Setting fire to this new "absinth" though, can hardly have made the taste significantly worse. Most experts in the field argue that Czech (and most other) fake absinths taste downright awful as they are, especially when compared with traditional, genuine absinthe, even in their modern forms.

Another country, and in this context quite an important one, that also escaped the absinthe bans was Czechoslovakia. When the so-called Velvet Revolution took place in 1989, the country’s enterprise picked up again after decades of state-communist oppression. One of the companies that began to emerge was a small distillery where the inventive Radomill Hill started producing his own version (?!) of absinthe, Hill’s Absinth, spelled without a final -e. (Picture to the right.) This distinctive spelling would later come to represent Czech, or so-called "bohemian style", absinths. But it isn’t just the name that gives away that these differ somewhat from the classic absinthes. Most of all, these Czech variants are produced without distillation and generally with essences. In addition, they often lack anise entirely (or even star anise), which means the drink does not turn cloudy (opalesce) when mixed with cold water. The bitter taste (one of the reasons modern absinthe gained a rather poor reputation in terms of flavor) and the absence of opalescence may have been contributing factors to the now infamous abuse (!) of setting absinthe on fire. This new "absinth ritual", however, has no historical basis whatsoever, and no evidence has been found that it was practiced at all before the 1990s. Setting fire to this new "absinth" though, can hardly have made the taste significantly worse. Most experts in the field argue that Czech (and most other) fake absinths taste downright awful as they are, especially when compared with traditional, genuine absinthe, even in their modern forms.

(It should be made clear that in more recent times the Czech Republic has also gained at least one producer (ŽUSY, s.r.o.) that makes absinthe the way absinthe is supposed to be made—that is, through distillation, with natural ingredients and without additives. I have personally drunk their Absinthe St. Antoine and can truly attest that it is absinthe, tasting exactly as absinthe should, with nothing strange about it. It is, moreover, an excellent absinthe. At the same time, it is by no means only in the Czech Republic that substandard "crapsinthe" is produced. Sweden, and even France, have had (or still have) their fair share of such inferior producers.)

You can read more about so-called Czech or Bohemian crapsinth here at The Wormwood Society. (You’ll need to scroll down a bit and read under the heading "What’s wrong with Czech style absinth?")

Czech crapsinths, as I prefer to call them for lack of a better term, were pushed fairly aggressively in the United Kingdom, where an importer (Bohemia Beer House Ltd.—later BBH Spirits) discovered that the country actually lacked a general, statutory ban on absinthe. They therefore began importing Hill’s Absinth in 1998. The rumors about absinthe’s supposed dangers, together with the new and admittedly somewhat cool (though at the same time rather dangerous) fire ritual, gave the whole thing momentum. Connoisseurs and absintheurs frowned, but at the same time it became something of a hype to travel to Prague to drink (and set fire to) what people believed was absinthe.

All of this, however, was not entirely bad!

The Czech crapsinths did, after all, bring the positive effect of increasing interest in absinthe. Some thought they knew what absinthe was (a bitter witch’s brew best set on fire) while others actually knew a bit more, and some began experimenting with both production and research. Connoisseurs and others with knowledge of classical and genuine absinthe started testing things based on old preserved recipes. At the same time, efforts began to push for the repeal of the bans that were still in place in various countries.

The story is far too long to be told in its entirety here, at least for now, but during the first decade of the 2000s, legislators around the world began to realize that absinthe is actually no more dangerous than, for example, Bäska droppar, Gammeldansk, Vermouth, or wormwood-spiced schnapps. (In fact, it may even be the opposite, at least in cases where, for example, one spices their own wormwood schnapps.) Ironically, fate played a role here, because in practice the EU had actually already approved absinthe in Europe without anyone really noticing. A 1988 EU directive regulating, among other things, the substance thujone in various food products established that levels below 35 mg/kg are considered completely safe. The result, in short, is that we can once again enjoy classic, good, and genuine absinthe around the world. At the same time, those of us who love absinthe still have to contend with the various offshoots (crapsinths) that compete for the name. Gwydion Stone at The Wormwood Society has suggested that these offshoots might better be called Wormwood Vodka (or something similar), and I am inclined to agree. But here in Sweden, for example, this would probably clash a bit with traditional wormwood-spiced schnapps.

Some Practical Advice (for those who want to or are going to buy absinthe)

To get hold of a good absinthe and avoid being deceived, it is first and foremost quite important to actually read up or find out the facts. I recommend the websites The Wormwood Society and absinthe.se (the latter in English though it's a Swedish site). There, you’ll mainly find reviews that are invaluable when trying to determine whether a particular brand is genuine or not. You will also usually find ratings given to different brands, both by experts and amateurs.

It’s not easy to know what is what, especially not here in Europe. There are no laws, except in Switzerland, so far—that regulate what may actually be called absinthe. Such rules do not exist in the U.S. either, but there producers are at least required to declare which additives (mainly E-numbers) are in their products. This allows you to get an idea of whether there are artificial substances in the drink, which would strongly indicate that it is not entirely genuine absinthe.

The image on the right illustrates quite well the jungle that exists when trying to buy absinthe. On some fake products, it is fairly obvious that they are indeed fakes, but sometimes it is much harder to tell. That’s why it certainly doesn’t hurt to do some research and read up a bit, at least as long as no good and effective trademark protection exists. (I'm sorry that the labels are in Swedish, but it says Absinthes to the left and Cheats to the right.)

The image on the right illustrates quite well the jungle that exists when trying to buy absinthe. On some fake products, it is fairly obvious that they are indeed fakes, but sometimes it is much harder to tell. That’s why it certainly doesn’t hurt to do some research and read up a bit, at least as long as no good and effective trademark protection exists. (I'm sorry that the labels are in Swedish, but it says Absinthes to the left and Cheats to the right.)

Some people believe that the extremely bitter and rubber-like taste they may have encountered at some point represents genuine absinthe. However, that is not the case! A good, authentic, and genuine absinthe tastes fresh and lively, and the first flavor you usually notice is that of anise, which makes the drink reminiscent of Ouzo, Raki, Pernod, Pastis, etc. In other words, for lack of a better description, somewhat licorice-like. (Licorice, however, is fundamentally not the same flavor-wise as anise.) Beyond the anise, you can quite clearly detect other flavors that give absinthe a much more herbal, sometimes even slightly spicy, or perhaps a somewhat floral and even perfumed character. Wormwood (without which absinthe is, by definition, not absinthe) is mainly perceived as a lightly dry, slightly "earthy" and perhaps a little astringent note, in some cases possibly even as a mild bitterness. The biggest problem with various fake versions (crapsinth) is that the bitterness dominates. This never happens in genuine absinthe because the bitterness largely disappears during distillation. Authentic absinthe is produced, as described previously and which I will now repeat, by letting at least wormwood, anise, and fennel steep in strong neutral spirit (around 80–90% (160–180 proof) for a while. The resulting macerate is then distilled, and this step is absolutely crucial. Finally, the absinthe is flavored with other herbs, such as pontica, hyssop, mint, etc., and green plant parts give absinthe its possible color. Genuine absinthe is never artificially colored; it gets its color naturally from green plant parts, as mentioned. Sugar or other sweeteners are also never added; the consumer can sweeten it according to taste. Any sweeteners, including sugar, are considered additives.

In short:

A genuine absinthe is a distillate of spirit, herbs (of which at least three must be wormwood, anise, and fennel), and water — nothing else.

So what can you try to watch out for if you don’t have time, or for some reason don’t want to do research? Well, in that case, you should avoid absinthes that look artificially colored. A "chemical" blue-green hue reminiscent of mouthwash (see the picture of Hill’s Absinth above) usually indicates that it is an inferior product or even a fake. The same goes for bright green, black, purple, and vivid red variants. There are, however, good and completely genuine absinthes with unusual colors (for example, red), but the risk of buying the wrong one is much higher the more artificial or striking the color appears.

Also, check the labels. If there is any E-number listed, it is likely not genuine absinthe. It might still taste reasonably okay, but the risk of it tasting terrible is definitely higher if E-numbers appear on the label.

Furthermore, as mentioned, you should avoid sweetened absinthe as well (pre-sweetened or added sugar).

To summarize:

No chemical notations, no E-numbers, and no added sweeteners. The color should look natural, sometimes even slightly yellow-brown. If the bottle also says “distilled” and “natural ingredients,” that’s of course useful information and a plus. And whatever you do, avoid anything labeled "bohemian style". This has nothing to do with Parisian bohemians of the Belle Époque; in this context, it refers to Bohemia (a region in the Czech Republic).

BIG WARNING at the end:

If labels or producers mention anything about the thujone content or level, you can be absolutely certain that it is not genuine absinthe, or at least that they are trying to cash in on the false myths surrounding absinthe. The thujone content is completely irrelevant in this context! Producers who mention the maximum thujone level in their product, or otherwise boast about the thujone, simply do not know what they are talking about, and you will NOT (!) get any particularly different "experiences" from their flavored spirits. It might be slightly (!) better if a producer declares something like "legal thujone content", but the very best is, of course, to ignore the thujone content altogether.

So far, I’ve mostly written about green absinthe above (verte in French) though it can sometimes appear more brown than green due to sunlight breaking down the chlorophyll, without affecting the flavor, as far as I have heard and read. But there is, of course, also completely colorless absinthe (blanche or la bleue). In addition, there are actually a few red ones (rouge), colored for example with hibiscus. In any case, these should also be considered genuine absinthe. Especially the colorless varieties. The naturally colored reds are what I would call color variants, but they are at least not fake products — they are perfectly normal absinthes.

The Absinthe Ritual

Here I’ll let Gwydion Stone from The Wormwood Society demonstrate the classic way to prepare a glass of absinthe (around 3:35) instead of writing a lot of "murky" text and illustrating it with a bunch of pictures. In the video, which has been translated into Swedish and subtitled by me, both an absinthe fountain and a regular pitcher are used. First, however, Gwydion Stone briefly talks about absinthe and its history before showing how the classic so-called absinthe ritual is performed. The video is an episode of "Inspired Sips with The Liquid Muse".

Here I’ll let Gwydion Stone from The Wormwood Society demonstrate the classic way to prepare a glass of absinthe (around 3:35) instead of writing a lot of "murky" text and illustrating it with a bunch of pictures. In the video, which has been translated into Swedish and subtitled by me, both an absinthe fountain and a regular pitcher are used. First, however, Gwydion Stone briefly talks about absinthe and its history before showing how the classic so-called absinthe ritual is performed. The video is an episode of "Inspired Sips with The Liquid Muse".

(Click on the image to see the video.)

The American absinthe ban mentioned around 1:37 was lifted by the TTB in 2007, which would suggest that the video was produced in 2009 or 2010.

PS:

Regarding modern Pernod Absinthe, which I wrote about earlier on the history page, it is not the same company as during the Belle Époque. Today, there is no company called Pernod Fils. Modern Pernod Absinthe is produced by the massive multinational spirits corporation Pernod Ricard. According to knowledgeable connoisseurs, it is not at all the same absinthe either. (Personally, I have only tried the Tarragona variant from the 1950s or -60s so far, but the leap from that to modern Pernod Absinthe is quite large.) Recently, however, they have improved the modern product, quite significantly one might say, so that it is now actually a genuine, authentic absinthe. Pernod Ricard, however, wants to give the impression that their modern absinthe is the same as the Absinthe Pernod Fils that was immensely popular between roughly 1860 and 1915, but they are certainly a long way from that... If you still feel like trying their (real) absinthe, look for Pernod Absinthe –

On the next page, I tell you about how I became interested in absinthe and how I’ve managed to navigate "the absinthe jungle" reasonably well. So, it's about my own experiences and reflections.