PGP encryption

On this page, I go through the absolute basics of encryption using GPG in the program Kleopatra, which is part of Gpg4win. But first, a bit about the concepts that are good to be familiar with.

(I'm sorry that all the images on this page are in Swedish. But I hope you'll be able to follow along anyhow.)

GPG (or GnuPG) is, in short, a program that uses the open standard (OpenPGP) for PGP (Pretty Good Privacy). PGP itself, the original, is nowadays a commercial product, but the same encryption principles are applied in GPG. Gpg4win is the main software suite for Windows to use GPG. For Mac users, however, I would recommend taking a look at GPGTools.

PGP itself was developed by Philip R. Zimmermann and released in 1991, to implement a new concept in encryption—namely, key pairs. A key pair consists of a private and a public key. The private key should be kept entirely to oneself and stored in a secure place. The public key, on the other hand, can be distributed more or less freely so that others can send you encrypted messages. Earlier encryption relied on using the same key to both encrypt and decrypt messages. However, this meant that the key (the only one, so to speak) could easily fall into the wrong hands. PGP, by contrast, meant that you didn’t have to risk anything like that since public keys can never be used to decode anything.

So how does encryption according to the PGP principle work?

Well. In order to send an encrypted message to someone, you need their public key. To decrypt a secret message, on the other hand, it must first and foremost have been encrypted with my public key (from the sender, that is), and then I unlock it with my private key. In other words: public keys are used to encrypt something for someone, and private keys are used to decrypt.

Why encrypt?

Well, this is something worth thinking about. At first, the answer is probably very simple: because you want to keep something secret. And primarily, this concerns your email. But why would you want to keep something secret, and from whom?

Think of it like this:

Sending unencrypted email is exactly the same as sending a postcard. Anyone who handles, processes, or comes into contact with it—both authorized and unauthorized—can read absolutely everything written there. Encrypting email, in short, means putting the message into an envelope that only the recipient may (and, in fact, can) open.

These days, a lot of people probably send all sorts of information and "letters" by email, and most use Gmail (from Google). The problem, however, is that everything sent by regular email is transmitted in plain text. That’s why it’s not a good idea to send anything you want to keep secret that way. Aunt Agda might not be able to read your email—unless she gets hold of your login details—but apart from that, pretty much anyone can access your messages. In particular, Google (in this case) can read all your (unencrypted) emails. But if you encrypt, you can be sure that only you and the recipient know the contents. No one else.

Encryption (step by step)

Okay. Now it’s time to start applying email encryption, and here I describe the process step by step using Kleopatra (on Windows). I’d recommend that you follow the instructions on a larger screen since the images get a bit too cluttered on a smaller one, like a mobile screen.

Okay. Now it’s time to start applying email encryption, and here I describe the process step by step using Kleopatra (on Windows). I’d recommend that you follow the instructions on a larger screen since the images get a bit too cluttered on a smaller one, like a mobile screen.

The first thing to do is download and install the Gpg4win software suite, version 3.1.5 at the time of writing. (If you don’t want to pay or donate, just select $0.)

Note: If you’re running a user account without administrator rights on your computer, you should right-click on the installation file and choose "Run as administrator". Otherwise, for example, you won’t see the context menu options offered by the suite when/if you right-click on a file in Explorer.

During installation, I recommend deselecting the options for GPA and GpgOL (image 01). GPA is an alternative to Kleopatra, and in my opinion completely unnecessary if you’re using Kleopatra (as I’ll show here). GpgOL is an add-in for Outlook (Microsoft’s email program), but in my experience it causes quite a few issues and requires specific versions of Outlook. After installation, it will look like the image below on the left when you start the program (Kleopatra).

When the installation is complete, you should create a key pair by clicking the "New Key Pair" button (as shown in the image on the left), or alternatively by choosing the same option in the File menu. You’ll then be presented with this dialog box (image 03), where you fill in your name and the email address you want to use. Note that you should enter your real name and the email address you intend to use, otherwise it won’t work properly later on. If you click Advanced Settings, you can choose the encryption algorithm, whether your key should be used for signing, and when it should expire (image 04). My recommendation is to stick with the default settings of 2048-bit RSA encryption and enable signing. If you want, you can also uncheck the option that makes the key pair valid only for a certain time—which I recommend doing. However, setting an expiration date can be useful if you plan to publish your public key on a key server.

When the installation is complete, you should create a key pair by clicking the "New Key Pair" button (as shown in the image on the left), or alternatively by choosing the same option in the File menu. You’ll then be presented with this dialog box (image 03), where you fill in your name and the email address you want to use. Note that you should enter your real name and the email address you intend to use, otherwise it won’t work properly later on. If you click Advanced Settings, you can choose the encryption algorithm, whether your key should be used for signing, and when it should expire (image 04). My recommendation is to stick with the default settings of 2048-bit RSA encryption and enable signing. If you want, you can also uncheck the option that makes the key pair valid only for a certain time—which I recommend doing. However, setting an expiration date can be useful if you plan to publish your public key on a key server.

The next step in the wizard is to review the parameters you selected (image 05). If everything looks correct, click Create. You’ll then be asked to set a password. Remember to choose a good, strong password (not something like "1234", "monkey" or "password", though of course it’s up to you) and make sure you don’t forget it.

At this point (image 06), I strongly recommend making a backup of your key pair and storing the file in a safe place. You can choose the location (and filename) by clicking the folder icon on the right (image 07). If you need to back it up later, you can do so via the File menu (image 08). Just remember to first select your own key in the list—which I forgot to do when creating the screenshot. Also note that the "Export…" menu option is used when you want to create, or export, your public key—the one that can be shared—while the "Export Secret Keys" option is used for personal backup. At this point, you’re ready to export your public key, which you can then send to someone else by email, for example, or upload to a website (as I chose to do, see below). This public key is what others need in order to send you encrypted email (or files or messages).

There we go. Now you’re ready to both receive and send encrypted messages.

Let’s say you want to send something (encrypted) to someone. First, you’ll need a file containing their public key. Save this file, then choose to import it into Kleopatra. You’ll then be asked how you want to certify it (image 09). This means you’re telling the program that the key you downloaded really does belong to the person who claims to have created it. This is especially important when verifying signatures—that is, making sure a message (or something else, like a program) really comes from the person you believe it does, and that it hasn’t been tampered with along the way. You certify by checking that the so-called fingerprint matches. If you know—or believe you know—that it’s correct, don’t forget to tick the box for "I have verified the fingerprint" (image 10). In the next step (image 11), I recommend certifying only for yourself… Of course, certification can also be done at a later time.

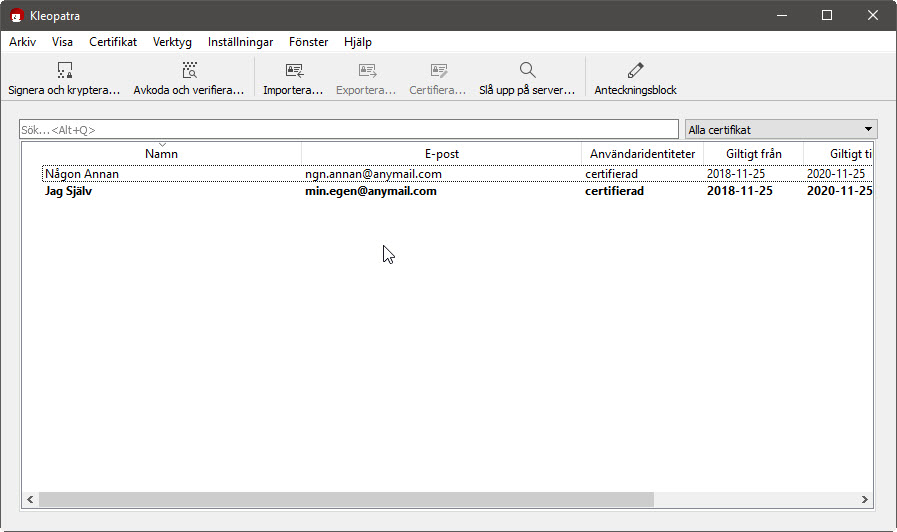

You now have an initial set of keys in the program (the image on the left). Your own, and someone else’s.

You now have an initial set of keys in the program (the image on the left). Your own, and someone else’s.

To send an encrypted message, you should not start typing in your email program or in Gmail on the web. There’s a risk that you might accidentally send something unencrypted, or that, for example, Google could read what you’re writing before it gets encrypted. Instead, you should click on the Notepad button. Then, select the Recipient tab (image 13) and check whether you want to sign the message and who you want to send it to. Sometimes you may need to start typing and then click on the correct choice so that the field is completely filled in. (Sometimes it’s also a good idea to encrypt it to yourself as well, so you can later decrypt it yourself. Otherwise, only the recipient can decrypt and read the contents.)

Next, go to the Notepad tab (image 14) where you write the actual message.

When you’ve finished writing, click the "Sign and encrypt notepad" button. Not the button above that just says "Sign and encrypt...", because that one is used instead when you want to encrypt, for example, files (images, etc.). After signing, you will also be prompted to enter your password to confirm that the sender is really you. The text will then be converted into encrypted text (image 15), and this is what you copy and then paste into the message field in your email program or on the web. Note that all of the text, starting from (and including) "-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----" and ending with "-----END PGP MESSAGE-----", must be selected and copied.

The same procedure applies if you receive something sent to you that is PGP-encrypted. In that case, you copy the encrypted text (in its entirety, as above or as shown in the image on the left) and paste it into the Notepad in Kleopatra. Then you click "Decrypt and verify notepad" (image 17), after which the text—as if by magic, and once you’ve entered your password—becomes readable again (image 18).

The same procedure applies if you receive something sent to you that is PGP-encrypted. In that case, you copy the encrypted text (in its entirety, as above or as shown in the image on the left) and paste it into the Notepad in Kleopatra. Then you click "Decrypt and verify notepad" (image 17), after which the text—as if by magic, and once you’ve entered your password—becomes readable again (image 18).

My own PGP key

Here you can download my public PGP key, which might come in handy if you want to send me something encrypted (cryptic). The key is available here both as an .asc file (you may need to right-click and choose "Save link as") and as a .txt file, that is, more or less in "plain text".

The key applies both to my Gmail address and to the email address published here on the site.

"The EFAIL flaw"

I have previously written a little about the so-called EFAIL vulnerability. However, this vulnerability does not apply to the encryption and especially decryption procedure I have described above. What EFAIL is about instead is a vulnerability in the implementation—that is, in how one decrypts messages, and in this case, email messages.

Through a so-called man-in-the-middle attack—meaning that a malicious hacker must first have access to the email in question—it is possible to alter an email that is read in HTML format and automatically decrypted, so that when it is decrypted, thanks to the modified HTML code, it is sent in plain text to the hacker. However, this requires three conditions: 1) That the message is read in HTML format. 2) That the message is intercepted along the way. And 3) That a so-called plugin is used in an email client (that is, an email program) which has this specific vulnerability... But in the procedure I have described, the decryption instead takes place outside of email clients (or web interfaces), and consequently, there is no danger. At least not when it comes to EFAIL.

Here I let Shannon Morse on ThreatWire explain the whole thing in a bit more detail, and with a bit more technolingo. Click on the image below to play the video (from YouTube).

More information can be found, among other places, at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (icij.org), where it is written, among other things, that "The EFAIL vulnerability isn’t a problem with the PGP protocol itself; instead it concerns the systems that automate the decryption process for users." And for those who want to know more specifically about EFAIL, I recommend efail.de for further reading.

As for whether email clients and plugins have since been patched, I’ll leave that unsaid, since I honestly don’t know (at the time of writing) and because the procedure described above is safe from EFAIL itself.

Some reflection

Yes. That’s what I’ve chosen to call this "disclaimer". Because there are, in fact, some things to keep in mind when choosing to encrypt emails and messages.

The first is that no so-called metadata is protected or encrypted. In short, this means that authorities and others can easily see who has communicated with whom, when it happened, probably the locations based on IP addresses and such, and—most importantly—the so-called subject line. That is not encrypted.

Furthermore, one should probably communicate in encrypted form with a few caveats. Let’s consider how secure/encrypted communication may appear from an authority’s perspective. Encrypted communication can, after all, be about anything—from secret cooking recipes to recipes for, or planning of, far more malicious things. But how are authorities supposed to know what is what? That’s where metadata comes in. Therefore, there may be reasons not to communicate with just anyone, even if the information is purely private or only about cooking recipes. The communication itself becomes quite interesting if it turns out that the person you are communicating with (encrypted, that is) is in other contexts known to communicate about truly illegal and "shady" things. In that case, it simply means that you might end up on some authority’s radar, so to speak. Personally, I take the view that as long as I’m not discussing, say, drug or bomb recipes, or planning some act of violence, I have nothing to fear or be ashamed of. But at the same time, I don’t encrypt completely unnecessarily, and I do make some considerations about who I communicate with in encrypted form—and, of course, about what I communicate.

These things may sound a little alarming. But at the same time, one should remember that people usually put regular letters in an envelope and even seal them. I believe the same should apply to email, at least as long as you think what you’re sending shouldn’t be accessible to just anyone. Besides, a great deal of internet traffic is already encrypted. All communication with web addresses that have the prefix https is, for example, sent in encrypted form. So the fact that some email is sent with PGP encryption may simply "get lost in the noise", so to speak.

The next page it's about the messaging app Signal.